Brazilian Variations - essay

The crisis of democracy in Brazil in the late 2010s began to materialize with the soft coup that put Dilma Rousseff out of office in 2016 and would eventually become epitomized by the political persecution of her predecessor—the then former president who is currently serving his third term—Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva…

Disponibilité: En stock

The crisis of democracy in Brazil in the late 2010s began to materialize with the soft coup that put Dilma Rousseff out of office in 2016 and would eventually become epitomized by the political persecution of her predecessor—the then former president who is currently serving his third term—Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

During the short presidency of Michel Temer (2016-2018), this sociopolitical crisis in the largest nation in South America presented profound connections with those that were then taking place in neighbouring countries. After years of progress in the development of sovereignty both on an individual and a national level—a process which was steadily advanced by the generation of progressive South American administrations of the early 21st century and their respective movements—citizens would again see a series of governments with strong authoritarian traits resurging throughout the continent. These oppressive forces would darken horizons with their overt disregard for the rule of law and human dignity. The various forms in which this authoritarianism manifested itself in the different scenarios in the region were, in many ways, novelties, yet these political forms were also the continuation of long-standing lineages, systems, and processes that have oppressed South Americans for centuries.

Brazilian Variations - essay

- 162 pages

- Dimensions : 140x205 mm mm

- Type : livre

- Couverture : softcover

- Poids : 850

- ISBN : 978-2-87593-569-4

- Maison d'édition : SAMSA Editions

Marcos Bertucelli (GB)

Marcos Bertucelli is an Argentinian visual artist, educator, and researcher who resides in Brussels, Belgium. His theoretical work focuses mainly on aesthetics, history, and political theory. He has taught visual arts and art history both inside and outside systemic education, and currently directs the nomadic educational project Las Islas. Bertucelli studied at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Prilidiano Pueyrredón in Buenos Aires, the Facultat de Belles Arts at the Universitat de Barcelona, and the Ruskin School of Art at the University of Oxford.

En savoir plusDernières parutions

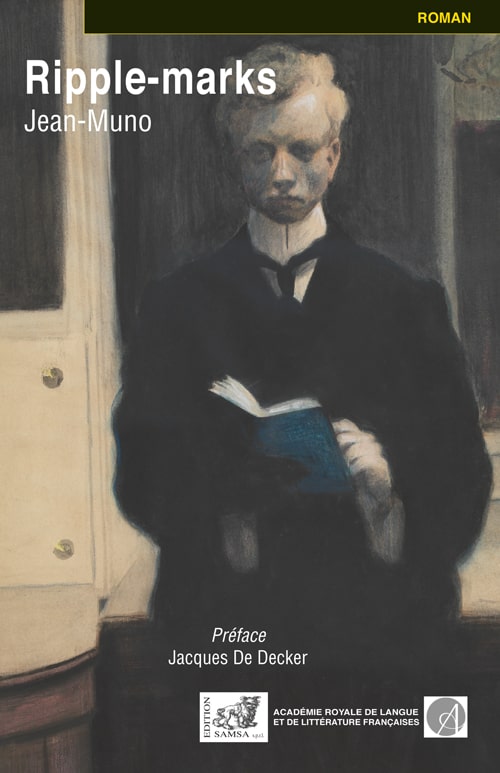

Ripple-marks (1976) est peut-être le plus grave des livres de Muno.

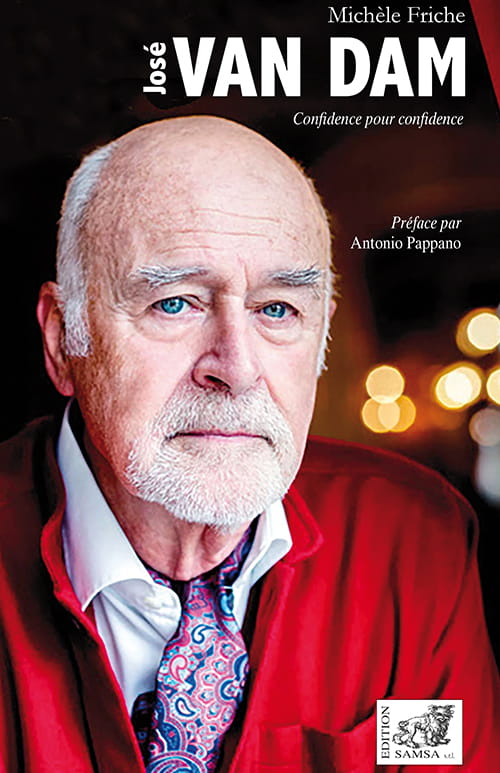

Le livre, tel une perle dans un écrin lyrique, se parcourt avec bonheur et nous rend plus proche ce magnifique chanteur universellement admiré. On y découvre la relation fusionnelle qui unit les héros d’opéra, leurs chants et l’homme qui leur prête sa voix.

Nous savons que les hommes remarquables et les personnages qu’ils incarnent ne meurent jamais tout à fait. Ces confidences en sont la preuve. « Nous n’existons que par ce que nous faisons », disait-il. José Van Dam a mis le point final à ce livre, avant de sortir côté jardin, refermant doucement la porte derrière lui, le 17 février 2026. Il nous laisse bien seuls à méditer dans le silence vibrant de ces pages.